Every year I hear people say “this is the year of automation!” And every year, for a variety of reasons, I see delivery fall short of expectations. While automated build pipelines are now the norm across enterprises, the range of possibilities for delivering business value via automation is still mostly untapped with the immensity of the QA automation backlog being one of the most obvious examples. The opportunities to drive robotic process automation (RPA) deep into the enterprise are so vast, that we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the appetite for RPA capped by MuleSoft’s acquisition of Servicetrace.

Despite the advances in democratizing automation technology, enterprises still need a strategy to address the resistance to automation due to concerns ranging from “that’s not automatable” to “they’re coming for our jobs.”

Automation evangelists have struggled to create a forward-looking mindset that is centered around growth and transformation since the industrial revolution. In each wave of automation, resistance from those impacted by the efforts fall into two categories:

- People generally reject change grounded in long-term self interest when they’re drowning in the here and now.

- There is not enough trust in automation to deter fears people’s jobs will be impacted once automation work is completed.

In looking at the friction points above, it’s important to take note that each of them are human-based rather than being technology feasibility blockers. These human-centered problems point to a generic truth many IT veterans know by heart — “technology doesn’t solve problems, people do.” What this aphorism tells us is that maybe we’ve all been framing and talking about automation too much in technology and business terms and not enough in human and ethical frames.

The ethical conflicts between humanism and technology-based progress first surfaced when Mary Shelley wrote what is often referred to as the first science fiction novel in 1818 – Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The themes of this book have stayed relevant over time, popping up through the works of John Steinbeck (most notably in The Grapes of Wrath) and into modern times with the seemingly endless array of Terminator films that tell of an endless war between robots and humans.

In an effort to solve this recurring puzzle of robotic resistance and friction, let’s look at a few examples of industry-wide automation initiatives to see if we can distill a framework for automation adoption that is aligned with both:

- The sentiments of the people impacted by automation.

- The effort to drive improved business results through automation.

Of mice, men, and job evolution

The conversation on the importance and impact of automation technologies has never been more widespread than it is today as even the tasks reserved to creatives and knowledge workers are being targeted by the robot hordes. But rather than focus on the current debate, let’s turn our attention to some well documented examples of automation and the struggle for acceptance:

Case study 1: Disney’s rocky road to embrace CGI

In the early nineteen eighties, the Walt Disney company released Tron. The film did moderately well at the box office but fell short of the outsized expectations for what some thought was a significant landmark in filmmaking. The extensive use of CGI (computer-generated imagery) to achieve visual effects without hand-drawn animation.

As detailed in Netflix’s documentary, The Pixar Story, soon after Tron was released, a few people inside of Disney (most notably John Lasseter) saw the potential of CGI and how it would revolutionize animation and filmmaking and tried to drive Disney to invest in making this technology more affordable and usable by Disney filmmakers and animators.

Despite the promising technology, many stakeholders rebelled against this change with what was essentially a desire to hold onto “the way we’ve always done things.” The fear of what computer automation would do to animators jobs and the craft of the filmmaking process was so intense that the technology was essentially shelved and John Lasseter was fired. Forty years later, CGI technology has become mainstream for filmmakers. There are now jobs related to animation, animated storytelling, and the continued automation of animation despite the fears that human animators would become obsolete.

Disney’s current domination of CGI-enhanced storytelling (Pixar, Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars franchises, reimagining Disney’s historic catalog, etc.) begs the question: “What could have been done to temper the fear of change for Disney to embrace the technology and process changes earlier without having to comeback and acquire the capabilities via purchasing Pixar, Lucasfilm, and Marvel?”

Case study 2: The great unforgetting

More recently in 2009, John Allspaw and Paul Hammond helped the fledgling movement known now as DevOps go viral. Their talk on how to build and deploy automations to achieve more than 10 deployments a day at flickr was a call to arms for operations professionals around the world. They wanted to end the “throw the pig over the wall” nonsense. While many individuals saw this as revolutionary innovation, there were other types of reactions as well.

Some systems veterans who had been using automation technologies for years said it was time for enterprises to wake up and listen to the concerns of teams that this was overly simplified as cost centers distracted company leadership from delivering top-line revenue growth.

A vocal contingent of operations and quality professionals actively fought against the change — similar to the resistance from the animators at Disney 30 years prior. The objections ranged from disbelief (“you can’t safely automate X”) to financial (“why should the business fund something that doesn’t produce revenue?”) but more often than not, had a grounding in what can be considered as a misguided concern for job obsolescence.

Just over a decade later, the demand for DevOps and cloud infrastructure professionals adept in automation is staggering, again begging the question: “What could have been done to temper the fear of change to embrace automation earlier and progress in their technology careers?”

There are two things each of these scenarios have in common:

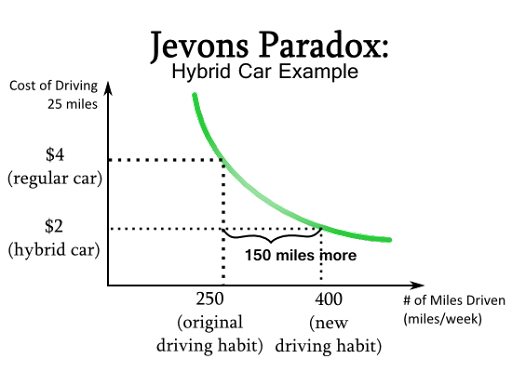

- A lack of awareness and/or acceptance regarding Jevon’s paradox. This states that the increases in the efficiency of a resource actually lead to an increased rate of consumption of said resource through increased demand. While it may seem hard to understand in the abstract, it’s close to common sense when you consider it in terms that relate to an individual.

For example, if you bought a car that got more miles per gallon than your current vehicle, you would likely drive it a bit more given that the cost of driving had dropped. Thus, automation should actually create more demand for the roles being automated.

Figure 1 – Jevons Paradox Example

This specific phenomenon where demand goes up in response to resource efficiency is something that neither of the above groups considered and/or believed when fretting over their own job security. While it is true that not every automation effort is guaranteed to create jobs in the domain where the automation is taking place, many economists and experts have concluded that automation — in the domain of IT — creates more jobs than it eliminates.

- The changes ushered in via automation were inevitable once a sufficient number of people can see how available automation capabilities could be applied to create a new operating model for the work context.

Steering clear of the grapes of wrath

When looking at the past alongside the present, a few truths emerge:

- The trend to systematically unlock and integrate data via technology is inevitable and will continue to accelerate.

- The trend to systematically unlock productivity via automating business processes is inevitable and will continue to accelerate.

- Many people in the roles impacted by the automation will resist the inevitable despite the encouragement of those with vision.

When considering these factors, it is hard not to be flummoxed. It is at this point that we should look a bit deeper at the historical struggles against job automation to see if there are opportunities to bypass the reflexive resistance inspired by fears of job security.

One commonality of the earlier case studies is that the stated goal of the technology-driven automation efforts was to remake the disciplines they affected with a better way of operating on the other side of automation. This innocuous aspect of how evangelists have socialized their vision, may reveal a different approach to automating the business.

Could we side-step the torches and pitchforks by changing our objectives from longer-term wins that people don’t believe in and focus instead on short-term alleviation of pain that they are all too familiar with? Rather than aiming to “automate roles/jobs” into a promised “higher-value plane,” can we aim to “automate the administrivia” that prevents people and teams from making progress on the efforts they are engaged in? An incremental approach model has the potential to to give teams:

- Something more concrete to work on rather than the broad call to “automate all the things.”

- An evolutionary approach to delivering automated business capabilities that doesn’t smell like job commoditization.

- A path to stakeholder value by using APIs as junction points to stitch together a digital stream of processes leading up to decisions.

This strategy model to incrementally automate the business has four steps:

- Unlock your data assets

Using MuleSoft’s Anypoint Exchange, your enterprise can:

- Provide programmatic and secure access to all systems of record by default.

- Provide programmatic and secure access to value chain activities and processes by default.

- Enable governed self-service to data assets via need-to-know and want-to-know filters.

- Automate administrivia

Using newer offerings like MuleSoft’s Composer and our recently acquired RPA tooling, your teams can:

- Identify low complexity, linked processes ripe for RPA automation.

- Provide low complexity integration capabilities to non-coders via no/low code tooling.

- Build new ways of working that encourage using fixed costs to drive down variable costs.

- Unlock context building

Take advantage of the Salesforce ecosystem by leveraging Tableau to:

- Engage in research to identify analysis and synthesis activities.

- Aggregate siloed data sets that represent a 360 view of decision context.

- Root out manual data aggregation and integration activities en masse.

- Automate decision making

Make use of systematized clarity with advanced tools like Salesforce Einstein by:

- Identify low complexity, low risk decisions that can be systematized.

- Train ML bots and decision support systems to spot patterns and outliers.

- Migrate decisions from manual process through button pushing to “always-on.”

This four-step process can help enterprises leverage tooling to collapse and package high-touch, multi-step, low complexity processes into low-touch, digitally requestable, single-step, automations. The resulting improvements to “flow” will kick the Jevons impact into gear in ways that increases:

- The value at stake in automating the higher complexity integration processes.

- The clarity and practicality of steps required to automate the higher complexity integration processes.

Progress need not always look like destruction

When iteratively repeated, this process has the potential to reduce the cycle times of bottleneck processes, improve data and decision quality, improve organizational alignment along with team morale and engagement, and — ultimately — improve the efficacy of the wider enterprise.

Ultimately, the four-step process reveals a path to systematically enable data-driven decision making within the enterprise. With this process in hand, we can help teams and business leaders grow more comfortable with automated decision-making. In the same manner that smart-phones made humans both grateful and dependent on GPS-based navigation, we can help teams and business units use automated decision tools without thinking twice.

As decisions improve and organizations grow, teams that are comfortable with their robotic assistants should naturally look to expand their use — because the learning curve is behind them. Just like Jevons predicts, improved efficiency will increase demand.

In this new frame, however, leadership will be responsible to help answer the question of “how much automation is too much?” In part two of this article, we’ll lay out some rules of the road to help guide the automators in creating a work environment safe for both humans and robots.

To learn more about the role of automation in the modern enterprise, download our CIO guide to enabling business automation eBook.