Last Updated August 22, 2016: I created a series of follow-up posts on this topic (but read this post first):

- ESB or not to ESB revisited – Part 1. What is an ESB?

- ESB or not to ESB revisited – Part 2. ESB and Hub n’ Spoke Architectures

- ESB or not to ESB revisited – Part 3, API Layer and Grid Processing Architecture

Many of us have had to ponder this question. Technology selection is notoriously difficult in the enterprise space since the criteria and complexity of the problem is often not fully understood until later in the development process.

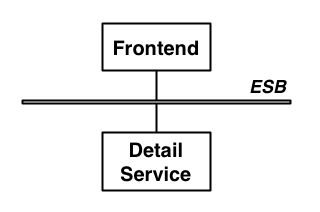

There is an interesting post from ThoughtWorker Erik Dörnenburg with the unfortunate title “Making the ESB pain Visible”. Erik provides a real-world example of when not to use an ESB citing that –

“Based on conversations with the project sponsors I began to suspect that at least the introduction of the ESB was a case of RDD, ie. Resume-Driven Development, development in which key choices are made with only one question in mind: how good does it look on my CV? Talking to the developers I learned that the ESB had introduced “nothing but pain.” But how could something as simple as the architecture in the above diagram cause such pain to the developers? Was this really another case of architect’s dream, developer’s nightmare?”

Later, Erik quite rightly points out that an ESB architecture should not have been used in this scenario. This is a fairly common problem for ESBs and enterprise technology like BPM/BPEL where the technology is not chosen for the right reasons, and then the technology gets blamed when the project struggles. Given that much of the enterprise software disillusionment, today stems from the incorrect usage of the technology I thought I’d offer some rough guidelines for selecting an ESB architecture.

ESB selection checklist

Mule and other ESBs offer real value in scenarios where there are at least a few integration points or at least 3 applications to integrate. They are also well suited to scenarios where loose coupling, scalability, and robustness are required.

Here is a quick ESB selection checklist –

- Are you integrating 3 or more applications/services? If you only need to communicate between 2 applications, using point-to-point integration is going to be easier.

- Will you really need to plug in more applications in the future? Try and avoid YNNI in your architecture. It’s better to keep things simple re-architect later if needed.

- Do you need to use more than one type of communication protocol? If you are just using HTTP/Web Services or just JMS, you’re not going to get any of the benefits if cross-protocol messaging and transformation that Mule provides.

- Do you need message routing capabilities such as forking and aggregating message flows, or content-based routing? Many applications do not need these capabilities.

- Do you need to publish services for consumption by other applications? This is a good fit for Mule as it provides a robust and scalable service container, but in Erik’s use case, all they needed was an HTTP client from their front-end Struts application.

- Do you have more than 10 applications to integrate? Avoid big-bang projects and consider breaking the project down into smaller parts. Pilot your architecture on just 3 or 4 systems first and iron out any wrinkles before impacting other systems.

- Do you really need the scalability of an ESB? It’s very easy to over-architect scalability requirements of an application. Mule scales down as well as up making it a popular choice for ‘building in’ scalability. However, there is a price to be paid for this since you are adding a new technology to the architecture.

- Do you understand exactly what you want to achieve with your architecture? Vendors often draw an ESB as a box in the middle with lots of applications hanging off it. In reality, it does not work like that. There is a lot of details that need to be understood first around the integration points, protocols, data formats, IT infrastructure, security, etc. Starting small helps to keep the scope of the problem manageable and keep the fuckupery to a minimum. Until you understand your architecture and scope it properly, you can’t really make a decision as to whether an ESB is right for you.

- Generally, always validate a product solution for your needs. Don’t choose an ESB or any other technology because –

- It will look good on my resume

- I don’t need the features today, but there is a remote chance that I _might_ in future

- I had a great golfing weekend with the head of sales

This checklist is not exhaustive, but will help clarify when not to use an ESB. Once you have decided that an ESB is a good fit for your project you’ll want to add additional selection criteria such as connectivity options, robustness, error management, service repository, performance, data support, etc. The important thing to remember is that there is no silver bullet for good architecture, and you need to know your architecture before making a technology decision.

With this checklist in mind, it’s easy to see that Erik’s example never needed an ESB architecture in the first place.

However, if the architecture looked something more like this, then an ESB would have probably been a good fit.

Choosing Mule

Obviously, as the creator of Mule I have some bias for wanting everyone to use Mule. However, it is critical to the continued success of Mule ESB that users understand when not to use an ESB architecture. Open source makes a lot of sense for enterprise software because projects need time to try out the technology and refine their proposed architecture. Having access to the product and source code helps a huge amount in this discovery process and allows the customer to make an informed decision.

In fact, the Mule adoption model hinges on the ability of the user to self-select Mule and approach us only when they need enterprise capabilities or support. This has been working very well for everyone involved. Customers get to do a proof of concept (PoC) with our product knowing that if they end up using it for a mission critical application that they can get enterprise 24×7 support. For MuleSource it means that we enable our customers to buy from us rather than us selling to them, so they always get what they want – this is a far cry from the old proprietary upfront license model that used to hold the enterprise market hostage.

Follow: @rossmason, @mulesoft

Update: I have started a series of follow-up posts on the topic of ESB or not to ESB that starts here.